Animal, vegetable, bacterial, and viral proteins are large linear polymers made up of hundreds, and sometimes even thousands, of subunits called amino acids.

The amino acid sequence, which is unique and genetically encoded, is called the polypeptide chain or primary structure. In the polypeptide chain, amino acids are linked in series by covalent bonds called peptide bonds.

The primary structure largely determines the three-dimensional structure, or conformation, of the protein.

Proteins are a large and diverse class of molecules. They are present in all living organisms, in all cellular compartments, and exhibit very different structures, even within the same cell type, where hundreds or even thousands of different proteins can be found, each performing a distinct function.

The great variety of functions they are able to perform derives from the ability of the polypeptide chain to fold into specific native three-dimensional structures, which also confer the capacity to bind different molecules. Proteins are therefore the primary means through which genetic information is expressed.

Summary: Key Points

- Definition: linear polymers made of amino acid chains linked by peptide bonds.

- Structural levels: protein organization is divided into primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures.

- Motifs and domains: globular proteins contain combinations of secondary structures (motifs) and stable functional units (domains).

- Biological functions: they act as enzymes (catalysts), structural components (collagen), transport proteins (hemoglobin), and defense molecules (antibodies).

- Determinism: the genetically encoded primary sequence dictates the protein’s three-dimensional conformation and specific biological activity.

- Complexes: proteins can interact to form macromolecular machines or multienzyme complexes to perform coordinated cellular tasks.

Contents

Historical background

As proteins are generally easier to isolate than lipids, nucleic acids, and polysaccharides, their study preceded that of other biomolecules and can be traced back to investigations of the chemical composition of albumins conducted by Jöns Jacob Berzelius, considered one of the fathers of modern chemistry, and Gerardus Johannes Mulder in 1839. By comparison, the role of nucleic acids in the transmission and expression of genetic information came to light in the 1940s, their catalytic role only in the 1980s, and the role of lipids in biological membranes in the 1960s.

The term protein derives from the Greek word proteios, meaning “primary” or “preeminent”, and was first suggested by Berzelius to Mulder. In fact, Berzelius believed that proteins might be the most important biological substances.

Protein structure

Like other biological macromolecules, proteins are made up of many small organic molecules, namely amino acids.

About 20 different amino acids have been identified which, according to the Fischer−Rosanoff convention, are present almost exclusively in the L form. Occasionally, D-amino acids have been found in certain bacterial proteins.

L-amino acids are bifunctional organic compounds, as they contain both a carboxyl group and an amino group attached to a central carbon atom, known as the α carbon; for this reason, they are also called L-α-amino acids. Each amino acid is characterized by a side chain, known as an R group, which, like the carboxyl and amino groups, is attached to the α carbon. The R group is responsible for the chemical properties of the amino acid, as it can vary in size, charge, shape, and reactivity.

During protein synthesis, the carboxyl group of one amino acid is covalently linked to the amino group of the incoming amino acid via a condensation reaction, which is catalyzed by specific enzymes, namely proteins with catalytic activity. During this reaction, a water molecule is released and a peptide bond is formed. The peptide bond is a rigid, planar, and very stable bond; indeed, at physiological pH and in the absence of external interventions, its lifetime is approximately 1,100 years. A linear polypeptide chain is formed by end-to-end bonds between adjacent amino acids.

In describing how polypeptide chains fold into their three-dimensional structures, it is useful to distinguish different levels of organization, namely primary, secondary, and supersecondary structures, domains, and tertiary and quaternary structures.

Note: the Fischer–Rosanoff convention is no longer widely used, except for carbohydrates and amino acids, having been largely replaced by the RS system, which allows unambiguous naming of molecules with chiral centers.

Primary structure

Bovine insulin was the first protein whose primary structure was determined, thanks to the work of Frederick Sanger.

The primary structure is the amino acid sequence of a protein, its lowest level of organization, and, as mentioned above, it is unique, genetically determined, and responsible for the three-dimensional structure and function of the protein. It can consist of 40 to over 4,000 amino acid residues.

The polypeptide chain has polarity, as its two ends are different: one end has a free amino group and is called the NH2-terminus, or amino terminus; the other has a free carboxyl group and is called the COOH-terminus, or carboxyl terminus. The two ends of the polypeptide chain are also known as the N-terminal end and the C-terminal end, to distinguish them from the amino and carboxyl groups present in the R groups. By convention, the N-terminal end is considered the beginning of the amino acid chain and is written on the left.

The primary structure is also of interest because, by comparing the same protein in different species, it is possible to identify variations that the corresponding gene has undergone, which are indicators of species divergence over the course of evolution.

The terms dipeptide, tripeptide, oligopeptide, and polypeptide are used to indicate chains of different lengths, consisting of 2, 3, fewer than 50, and more than 50 amino acids, respectively.

Secondary structure

The discovery of the secondary structure of proteins is due to the work of Linus Pauling and Robert Corey, who proposed two structures called the α-helix and the β-sheet, also known as the β-pleated sheet.

Protein secondary structure results from the formation of hydrogen bonds between contiguous parts of the polypeptide chain that have particular amino acid sequences. Therefore, it describes the spatial arrangement of amino acids that are not far apart along the primary structure.

In addition to the α-helix and β-sheet structures, other secondary structural elements have been identified, such as β-turns, γ-turns, and Ω loops, all belonging to a group known as reverse turns. These structures are often found where the polypeptide chain changes direction and are generally located on the surface of the molecule.

Approximately 32–38% of the amino acids in globular proteins are found within α-helix structures.

Structures beyond the secondary level are present only in globular proteins.

Supersecondary structures or motifs

Supersecondary structures are combinations of secondary structures that form regions of the molecule with characteristic three-dimensional structures and topology. These supersecondary structures are connected to one another by loop regions with undefined structure.

Among the most common motifs are the α–α corner, β-β corner, β-β hairpin, and β-α-β motif, the latter often present in proteins that bind RNA or DNA, as well as the 3β corner.

Domains

Domains are globular regions that result from combinations of supersecondary structures and fold independently of the rest of the polypeptide chain to form stable structures.

They consist of 40–400 amino acids, with the exception of motor and kinase domains, which are composed of a much larger number of amino acids.

Domains have been classified into three main groups, based on the secondary structures and motifs present:

- α-domains;

- β-domains;

- α/β-domains.

More than 1,000 domain families have been identified, and the members of each family are called homologues.

Very often, each domain has a specific function; that is, it represents a functional unit of the protein in which it is contained.

Proteins can consist of a single domain, typically smaller proteins, or of multiple domains. For example, chymotrypsin (EC 3.4.21.1), an enzyme involved in protein digestion, consists of a single domain, whereas papain (EC 3.4.22.2) is composed of two domains.

Tertiary structure

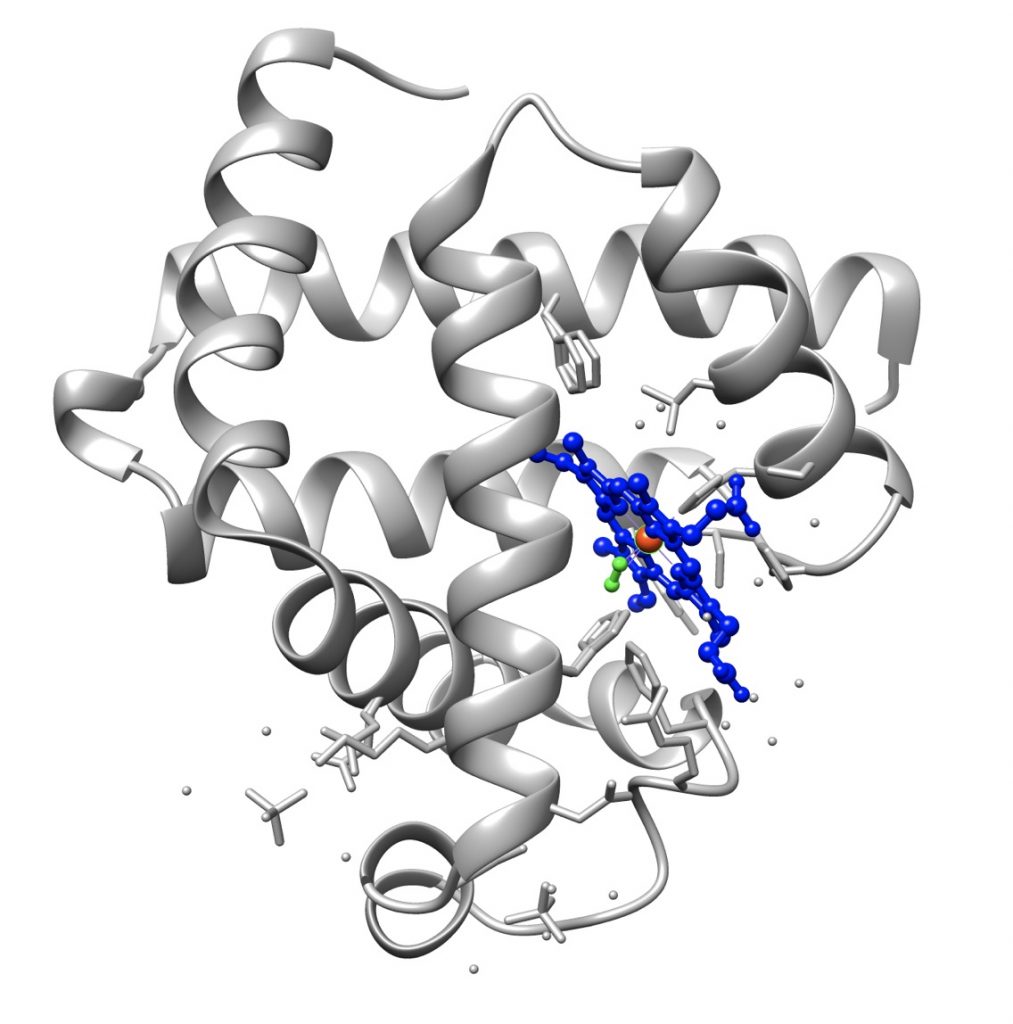

The tertiary structure, also called the native structure, is the three-dimensional structure of proteins and represents their biologically active form.

The first protein whose tertiary structure was determined was myoglobin, thanks to the work of John Kendrew.

Polypeptide chains are not rigid structures and spontaneously fold into distinct three-dimensional conformations that are largely determined by their amino acid sequence. The folding of the primary structure allows the transition from the one-dimensional world of the primary structure to the three-dimensional one of the protein.

In this level of organization, the folding of the polypeptide chain causes amino acids that are distant in the primary structure to come into close proximity; therefore, it concerns the three-dimensional arrangement of amino acids that are far apart along the primary sequence.

The tertiary structure of proteins, especially those consisting of more than 200 amino acids, is formed by several domains joined by short polypeptide segments. It is often stabilized by disulfide bridges between cysteine residues, which are formed after the molecule has attained its native conformation.

Not all globular proteins have a well-defined tertiary structure. An example is provided by milk caseins, whose polypeptide chains assume a disordered three-dimensional conformation, also known as a random coil structure. This disordered structure makes them highly susceptible to the action of intestinal proteases and therefore facilitates the release of the constituent amino acids. Another example of a random coil protein is elastin, one of the most abundant proteins in the body.

Quaternary structure

This level of structural organization describes how two or more polypeptide chains associate to form a single protein structure. Therefore, it refers to the spatial arrangement of the individual chains and the nature of the forces that bind them, such as:

- the hydrophobic effect, which is also the main driving force for protein folding;

- hydrogen bonds;

- van der Waals interactions;

- ionic interactions;

- covalent cross-links.

The resulting structure is called an oligomer or an oligomeric protein, and the constituent polypeptide chains, which may be identical or different, are called monomers or simply subunits.

In general, most intracellular proteins are oligomers, whereas most extracellular proteins are not. An example of a protein with a quaternary structure is hemoglobin.

This level of structure is obviously absent in globular proteins consisting of a single polypeptide chain, that is, in monomeric proteins.

Proteins can also interact with each other to form macromolecular machines in which, by acting synergistically, they perform functions that they would not be able to accomplish alone. An example is provided by multienzyme complexes, such as the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex.

Protein functions

Proteins perform an extraordinarily wide range of biological functions, reflecting both the structural versatility of the polypeptide chain and the chemical diversity of amino acid side chains. Their functions arise from the ability of proteins to fold into specific three-dimensional conformations and to interact selectively with other molecules, including small metabolites, macromolecules, and ions.

From a functional standpoint, proteins participate in virtually all biological processes. They act as:

- enzymes, catalyzing biochemical reactions essential for metabolism;

- transport proteins, enabling the movement of substances such as oxygen, lipids, and metal ions within the organism;

- structural components, providing mechanical support to cells and tissues;

- regulatory molecules, controlling processes such as gene expression, signal transduction, growth, and differentiation.

| Functional category | Typical examples |

|---|---|

| Enzymes | DNA polymerase, α-amylase |

| Transport proteins | Hemoglobin, GLUT4, transferrin |

| Structural proteins | Collagen, keratin, elastin |

| Defense proteins | Immunoglobulins (IgG), complement proteins |

| Contractile and motor proteins | Actin, myosin, kinesin |

| Regulatory proteins | Insulin, transcription factors |

| Energy source (under specific conditions) | Amino acids derived from protein catabolism |

Proteins also play key roles in defence mechanisms, for example through antibodies and other components of the immune system, and in the generation of movement, as in muscle contraction and intracellular transport. In addition, under specific physiological or pathological conditions, amino acids derived from protein catabolism may contribute to energy production, alongside carbohydrates and lipids, which represent the main macronutrients in human nutrition.

Given this functional diversity, one widely used approach to protein classification is based on the biological roles they perform. This functional classification provides a useful framework for understanding how protein structure is related to biological activity.

References

- Alberts B., Johnson A., Lewis J., Morgan D., Raff M., Roberts K., Walter P. Molecular biology of the cell. 7th Edition. Garland Science, Taylor & Francis Group, 2022.

- Berg J.M., Tymoczko J.L., Gatto J.G., Stryer L. Biochemistry. 9th Edition. W.H. Freeman and Company, 2019.

- Branden C., Tooze J. Introduction to protein structure. 2nd Edition. Garland Science, 1999. doi:10.1201/9781136969898

- Garrett R.H., Grisham C.M. Biochemistry. 7th Edition. Cengage Learning, 2023.

- Heilman D., Woski S., Voet D., Voet J.G., Pratt C.W. Fundamentals of biochemistry: life at the molecular level. 6th Edition. Wiley, 2023.

- Kessel A., Ben-Tal N. Introduction to proteins: structure, function, and motion. CRC Press, 2011.

- Nelson D.L., Cox M.M. Lehninger. Principles of biochemistry. 8th Edition. W.H. Freeman and Company, 2021.

- Petsko G.A., Ringe D. Protein structure and function. Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Rodwell V.W., Bender D.A., Botham K.M., Kennelly P.J., Weil P.A. Harper’s illustrated biochemistry. 31st Edition. McGraw-Hill, 2018.

- Stipanuk M.H., Caudill M.A. Biochemical, physiological, and molecular aspects of human nutrition. 4th Edition. St. Louis: Elsevier, 2018.